From: APPL. ENVIRON. MICROBIO

Volume/Issue: Unknown, missing beginning

Author: Unknown, missing beginning

A total of nine Cryptosporidium spp. were found in captive snakes, lizards and tortoises in this study. The most common parasites were C. serpentis and the Cryptosporidium desert monitor genotype. Both parasites were detected in snakes as well as lizards. Two other Cryptosporidium spp. previously reported in captive snakes, C. muris and the C. parvum mouse genotype, were also found in some snakes and one lizard. Another common Cryptosporidium parasite in mammals, the C. parvum bovine genotype, was also identified in six lizards from Switzerland. Four other Cryptosporidium spp. detected in this study, however, presented new Cryptosporidium spp.: a tortoise genotype identified in three tortoises, two new snake genotypes, and another new Cryptosporidium genotype from a lizzard, which was genetically distinct but was related to C. serpentis.

Oocysts of the C. parvum bovine and mouse genotypes and C. muris found in some of the snakes and lizards in this study probably do not represent true parasites of these animals. Instead, the oocysts were probably from rodents ingested by these carnivorous reptiles. This possibility was supported by the presence of organisms belonging to C. muris and the C. parvum mouse genotype in some of the feeder mice which were fed to snakes and some lizards in the Saint Louis Zoo. Although the C. parvum bovine genotype has not been found in mice in the United States, it has been previously reported in mice in Austrailia. Thus, oocysts of the C. parvum bovine genotype seen in lizards in Switzerland could also be from ingested prey or feeder mice. Previously, it has shown that oocysts of the C. parvum bovine genotype was not infectious to snakes. Nevertheless, the possibility of organisms belong to the C. parvum mouse and bovine genotypes and to C. muris infecting reptiles can only be totally rules out by careful biologic and genetic studies.

Because the four new Cryptosporidium spp. found in this study have never been reported in other animals before, they probably were true parasites of these captive reptiles.

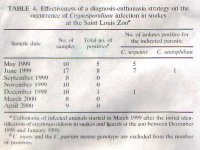

Currently there are no effective control strategies against Cryptosporidium in reptiles. In a small-scale study, it was demonstrated that snakes with clinical and subclinical Cryptosporidium could be effectively treated with hyperimmune bovine colostrum raised against C. parvum. A common control practice is to euthanize Cryptosporidium-infected snakes, which would prevent the spread of infection to other animals. This diagnosis-euthanasia strategy was apparently effective in the conrol of Cryptosporidium infection in snakes at the Saint Louis Zoo in this study. The effectiveness of the method was supported by te evident reduction of C. serpentis infection in snakes at the zoo. In addition to the premature death of infected animals, one problem with the control measure is the frequent presence of oocysts of C. muris and the C. parvum mouse genotype in snake because of the use of feeder mice as part of the diet. Because it is difficult to differentiate oocysts of the pathogenic C. serpentis from those of nonpathogenic Cryptosporidium spp. that merely pass through the gastrointestinal tract, the diagnosis-euthanasia control strategy would lead to the killing of uninfected animals.